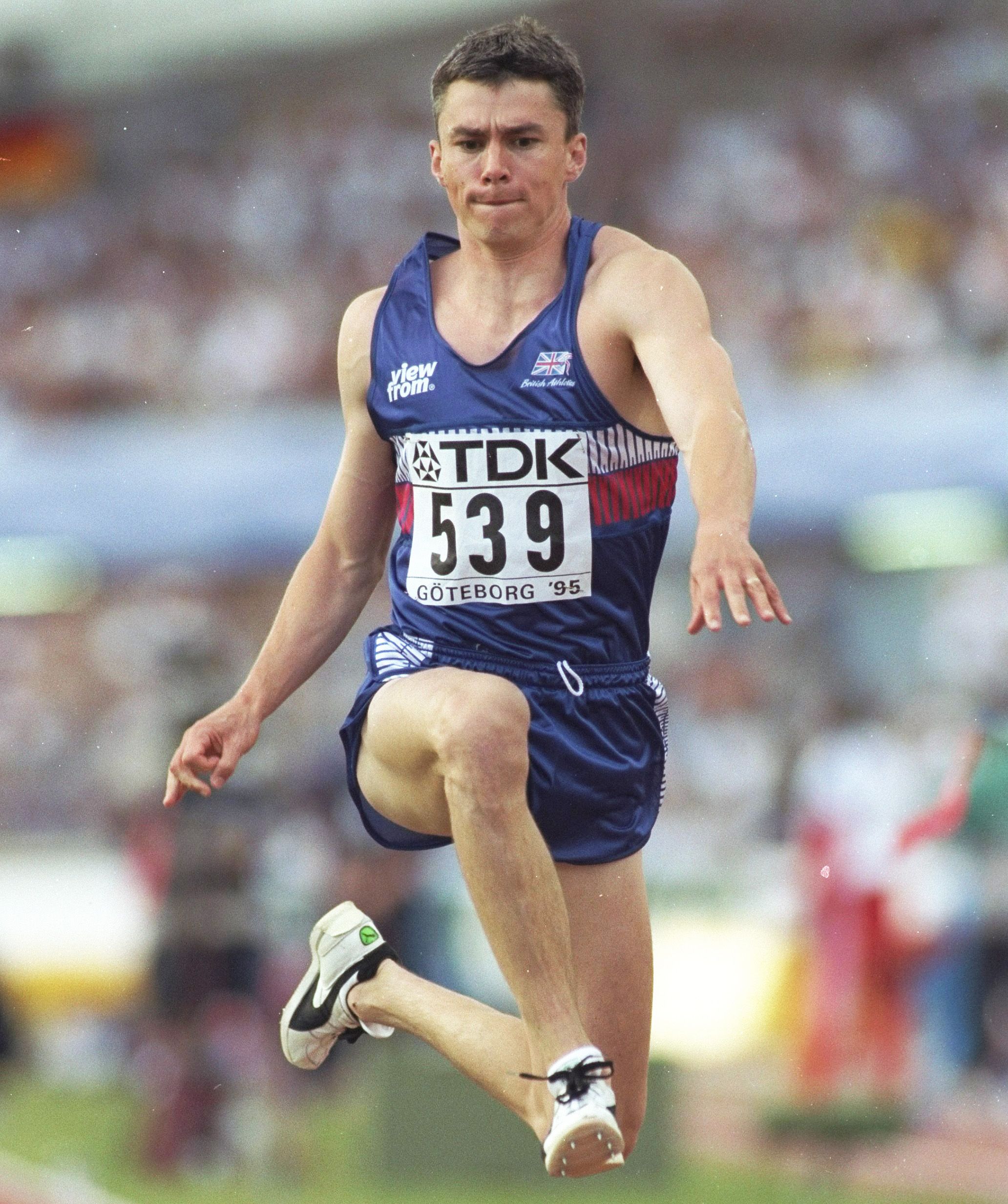

“I thought I would go on to break it again,” Jonathan Edwards said of his 18.29m world record leap from the 1995 World Championships in Gothenburg. “And no, I didn’t think it would last this long.”

It has now been 30 years since the Briton bounded out to two world records in the Swedish city. Speaking to World Athletics in 2021, Edwards looked back on his performance and explained how it still blows his mind that he accomplished what he did.

From the moment he opened his 1995 season with a 17.58m PB, Edwards knew he was in the form of his life. “The big thing about that season is that my technique was outstanding and the balance I had throughout the phases – which was brought about through me changing my technique and using a double arm action – gave me a much better position, particularly in the last phase.”

Early in the season, he sailed out to a wind-assisted 18.43m (2.4m/s) to win at the European Cup. He followed it with another wind-assisted leap beyond 18 metres (18.03m) in Gateshead and then set a world record of 17.98m in Salamanca.

Between then and the World Championships, he also landed a wind-assisted 18.08m in Sheffield – all of which only added to the pressure and expectation as he headed to Gothenburg.

“Although I’d broken the world record that year already, in my mind had I not won the World Championships, my season would have been regarded as a failure,” he said. “So I felt a huge amount of pressure because I’d never gone into a major championships expected to win. And not just expected to win but to break a world record as well, so I was petrified.

“I remember the wind was helpful and I knew the conditions were good. But I was as scared as you like, I thought I was going to mess it up, there was no guarantee I was going to win this thing.

“But alongside that feeling of being petrified, there was also a sense that I could jump a massive distance here,” he added. “I’d already jumped that 18.43m wind assisted, and I’d jumped a world record of 17.98m in Salamanca a few weeks beforehand, which was much less than I knew I was capable of. So there was also a real sense of excitement.”

He safely advanced to the final after jumping 17.46m in the qualifying round. USA’s Mike Conley, who had won the Olympic title three years prior with a jump of 18.17m that was just marginally over the allowable wind speed (2.1m/s), was also in the final, as were Dominica’s Jerome Romain, Bermuda’s Brian Wellman and Cuban duo Yoel Garcia and Yoelbi Quesada.

“With a technical event like the triple jump, when you’ve got three phases and the take-off, there are lots of things that could go wrong – no matter how good a form you’re in,” said Edwards. “But in this final, there was no holding back, no ‘let’s get a safe one in’. It was just run and jump and hope it’s good.”

His first leap was more than just ‘good’. Edwards flew down the runway, took off and then landed beyond the 18-metre mark. It took a few moments before his distance was confirmed at 18.16m, a world record and the first wind-legal jump beyond 18 metres.

“It was a celebration but also a huge amount of relief,” Edwards remembered of his reaction to that jump. “What strikes me now is how fast and flat I was. I had so much speed on the run-up, it took me much more in a horizontal than vertical direction when I took off. People have likened it to skimming stones, and these jumps on that day were very much like that.

“All I can remember is the feeling of ‘I’m not done yet in this competition’. Normally once I’d jump a big distance like that, I’d finish. But I still felt like there was more to do.”

About 20 minutes later, Edwards was on the runway again for the second round.

“I had a smile on my face and I pointed my finger,” he said. “I just wanted to enjoy the jump because I knew I probably wouldn’t have another one like it. I actually get quite emotional watching it.”

He once again nailed a great jump, this time improving on his opening effort. No sooner had he touched down in the sand than he was out of the pit once more, arms aloft and celebrating, knowing that he had gone farther than before.

There was another wait for the distance, though this time a less anxious one as the pressure was off and Edwards knew he had broken the record. He simply wanted the confirmation. And then it flashed up on the scoreboard: 18.29m.

“The moment I knew it was better was during the step because I just had to wait and then put my foot on the ground,” he said. “There’s just a brief moment when my front foot feathers a bit because the transfer from the hop to the step was better and I just had to stabilise a bit. As soon as I landed, I knew it was a world record, I knew it was further. That’s why I stood up and shrugged my shoulders as if to say ‘that’s another record’.“All I can remember is the feeling of ‘I’m not done yet in this competition’. Normally once I’d jump a big distance like that, I’d finish. But I still felt like there was more to do.”

About 20 minutes later, Edwards was on the runway again for the second round.

“I had a smile on my face and I pointed my finger,” he said. “I just wanted to enjoy the jump because I knew I probably wouldn’t have another one like it. I actually get quite emotional watching it.”

He once again nailed a great jump, this time improving on his opening effort. No sooner had he touched down in the sand than he was out of the pit once more, arms aloft and celebrating, knowing that he had gone farther than before.

There was another wait for the distance, though this time a less anxious one as the pressure was off and Edwards knew he had broken the record. He simply wanted the confirmation. And then it flashed up on the scoreboard: 18.29m.

“The moment I knew it was better was during the step because I just had to wait and then put my foot on the ground,” he said. “There’s just a brief moment when my front foot feathers a bit because the transfer from the hop to the step was better and I just had to stabilise a bit. As soon as I landed, I knew it was a world record, I knew it was further. That’s why I stood up and shrugged my shoulders as if to say ‘that’s another record’.

“I still had another 11 centimetres to spare on the board,” he added with a smile. “So if someone does ever break my world record, I’ll say actually I was 18.40m from take-off to landing.

“What I also knew in that instant – because I’d looked at this beforehand – is that 18.29m was just over 60 feet. So I’d broken the metric barrier of 18 metres and the imperial barrier of 60 feet. That was the front page of Track & Field News – ’60 Feet Goes’.”

Satisfied with his opening two efforts, Edwards passed the third and fourth rounds. He took his fifth-round jump, landing at 17.49m, but then passed his final attempt, his victory by this point assured.

“There’s always been a sense of ‘I can’t quite believe this has happened to me’,” said Edwards, who went on to win Olympic gold in 2000 before winning his second world title in 2001. “You grow up following your heroes on TV, and if you’re lucky enough you may see them in the stadium, and you feel very ordinary yourself. When you’re actually doing something that’s extraordinary, it’s hard to equate the two.“I still had another 11 centimetres to spare on the board,” he added with a smile. “So if someone does ever break my world record, I’ll say actually I was 18.40m from take-off to landing.

“What I also knew in that instant – because I’d looked at this beforehand – is that 18.29m was just over 60 feet. So I’d broken the metric barrier of 18 metres and the imperial barrier of 60 feet. That was the front page of Track & Field News – ’60 Feet Goes’.”

Satisfied with his opening two efforts, Edwards passed the third and fourth rounds. He took his fifth-round jump, landing at 17.49m, but then passed his final attempt, his victory by this point assured.

“There’s always been a sense of ‘I can’t quite believe this has happened to me’,” said Edwards, who went on to win Olympic gold in 2000 before winning his second world title in 2001. “You grow up following your heroes on TV, and if you’re lucky enough you may see them in the stadium, and you feel very ordinary yourself. When you’re actually doing something that’s extraordinary, it’s hard to equate the two.

“I almost appreciate it more now than I did at the time. I was in peak form and took it all in my stride. I enjoyed it all and it was fantastic, but I just don’t think I appreciated just how amazing it was.

“To do something in life and be categorically the best at it, it’s mind-blowing to be honest,” he added. “I can’t quite believe it happened to me.”

Jon Mulkeen for World Athletics

This feature was first published in 2021 and was updated to mark the 30th anniversary of the feat in 2025.

Latest6 months ago

Latest6 months ago

Football7 months ago

Football7 months ago

Football7 months ago

Football7 months ago

Rugby7 months ago

Rugby7 months ago

Football7 months ago

Football7 months ago

Football7 months ago

Football7 months ago

Football7 months ago

Football7 months ago

Rugby7 months ago

Rugby7 months ago